Bauhaus “Form follows

function” and “Less is more.”

The Bauhaus was an art school in Germany that combined crafts and

the fine arts and was famous for the approach to design that it publicised and

taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933.

The Bauhaus was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar with the idea of

creating a "total" work of art in which all arts, including

architecture, would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus had a profound

influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design,

interior design, industrial design, and typography.

The school existed in three German cities: Weimar from 1919

to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933, under three

different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, Hannes Meyer from

1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 until 1933, when the school

was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The Nazi

government claimed that it was a centre of communist intellectualism. The

changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus,

technique, instructors, and politics. Though the school was closed, the staff

continued to spread its idealistic precepts as they left Germany and emigrated all over the

world.

Walter Gropius wanted to create a new architectural style to

reflect this new era. His style in architecture and consumer goods was to be

functional, cheap and consistent with mass production. To these ends, Gropius

wanted to reunite art and craft to arrive at high-end functional products with

artistic merit. Gropius believed that in order to export innovative and high

quality goods, a new types of designers were needed and so was a new type of

art education. The school's philosophy stated that the artist should be trained

to work with the industry. Gropius explained his vision for a union of art and

design in the Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919), which described a utopian

craft guild combining architecture, sculpture, and painting into a single creative

expression. Gropius developed a craft-based curriculum that would turn out

artisans and designers capable of creating useful and beautiful objects

appropriate to this new system of living.

The Bauhaus combined elements of both fine arts and design education.

The curriculum commenced with a preliminary course that immersed the students,

who came from a diverse range of social and educational backgrounds, in the

study of materials, colour theory, and formal relationships in preparation for

more specialized studies. This preliminary course was often taught by visual

artists, including Paul Klee, Vasily Kandinsky, and Josef Albers, among others.

Following their immersion in Bauhaus theory, students

entered specialised workshops, which included metalworking, cabinetmaking,

weaving, pottery, typography, and wall painting. Although Gropius' initial aim

was a unification of the arts through craft, aspects of this approach proved

financially impractical. While maintaining the emphasis on craft, he

repositioned the goals of the Bauhaus in 1923, stressing the importance of

designing for mass production. It was at this time that the school adopted the

slogan "Art into Industry."

Along with Gropius, and many other artists and teachers,

both Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Herbert Bayer made significant contributions to the

development of graphic design. Among its many contributions to the development

of design, the Bauhaus taught typography as part of its curriculum and was

instrumental in the development of sans-serif typography, which they favoured

for its simplified geometric forms and as an alternative to the heavily ornate

German standard of blackletter typography.

Teachers and students at the Bauhaus talked and argued about

many topics: The place of art in an increasingly technological society; Were

the arts a matter of individual expression? Would a new, more egalitarian

society require a new, and perhaps more impersonal art? Could new forms of

expression be reconciled with capitalist methods of production?

To these questions they offered many answers, most often in

the form of actual objects and works of art, nearly all of them beautiful, some

masterworks, which now fill the galleries on the sixth floor of the Museum of

Modern Art, some impractical and today seen as unrealistic. The truth was that

there could never be any definitive answer. Today we question how the revolutionary

dreams of the Bauhaus became our everyday realities, and in some cases our

everyday banalities. Critics today look at the work of the Bauhaus and try and figure

out what went wrong. They ask how the glorious promise of the Bauhaus became so

terribly tarnished, and in so many respects misunderstood.

With a more rational and balanced view, critics today now

believe the Bauhaus means something very different. There is questioning and

doubt. Not everything was practical and perfect. The way the Bauhaus

represented the unifying power of geometry is something no longer generally

shared. Some believe that the school may indeed still be relevant, but only the

Expressionist early period, which is very different to what is normally

associated with the term "Bauhaus."

With a more rational and balanced view, critics today now

believe the Bauhaus means something very different. There is questioning and

doubt. Not everything was practical and perfect. The way the Bauhaus

represented the unifying power of geometry is something no longer generally

shared. Some believe that the school may indeed still be relevant, but only the

Expressionist early period, which is very different to what is normally

associated with the term "Bauhaus."

The Bauhaus idea always represented a compromise between

conflicting tendencies; a fanciful, utopian spirit was balanced against a more

practical-minded, forward-looking character.

In regards to women and the Bauhaus, there were constraints

imposed on the school’s supposedly liberated female faculty and students. The

Bauhaus at first was intended to be gender-blind. However, Gropius became

alarmed by what he saw as the disproportionate number of women in a student

body that never numbered more than 150 matriculates at any given moment, which

prompted him to steer women away from the supposedly “masculine” architecture

curriculum and toward the traditionally “feminine” crafts workshops.

One of the most interesting parts of the Bauhaus was Kandinsky

and the Yellow-Triangle, Blue-Circle, and Red-Square. It was Kandinsky's idea that

there are certain fundamental associations between colours and shapes he proposed Yellow-Triangle, Blue-Circle, and

Red-Square. These associations were formulated introspectively, however, he did

conduct his own survey at the Bauhaus in 1923 by distributing questionnaires to

his professorial colleagues and students, and found that many of his colleagues

agreed with his associations; notable exceptions were his contemporaries, Klee

and Schlemmer, who favoured different form-colour combinations. In fact,

Kandinsky had already embarked upon a similar attempt to identify colour form

associations while still in Russia

with the aim to provide the scientific underpinning for his own intuitions.

Kandinsky's Yellow-Triangle, Blue-Circle, and Red-Square

equation inspired several projects at the Bauhaus in the early 1920s. The most

interesting is an amazing baby cradle by Peter Keler. This unusual, and rather

dangerous looking design, illustrates the association between shapes and

colours, and shows that Kandinky's ideas have mainly only historical

significance and that forms and colours do not have universal meaning or

correspondence.

THE principles of the Bauhaus are in many ways no longer a

valid model for modern design. The emphasis on hard, uncompromising surfaces characteristic

of the Bauhaus can be alienating and remote. Something more comfortable is

needed for everyday use. The Bauhaus was responsible for many designs for

ordinary objects that look modern and that appear to do a particular task with

a minimum of fuss. This simplicity can be deceptive. Often, in order to attain

the purified line, essential elements have been left out.

The avant-garde pushes the

boundaries of what is accepted as the norm. The Bauhaus confronted tradition

and developed new ways of doing things, but struggled to legitimise their new

ideas. The rhetoric created by change can be more powerful than the

changes themselves. If the rhetoric is really good, with lots of catch-phrases

and easy concepts such as 'form follows function', and 'less is more', it can

take on a life of its own. The Bauhaus had, if nothing else, terrific rhetoric.

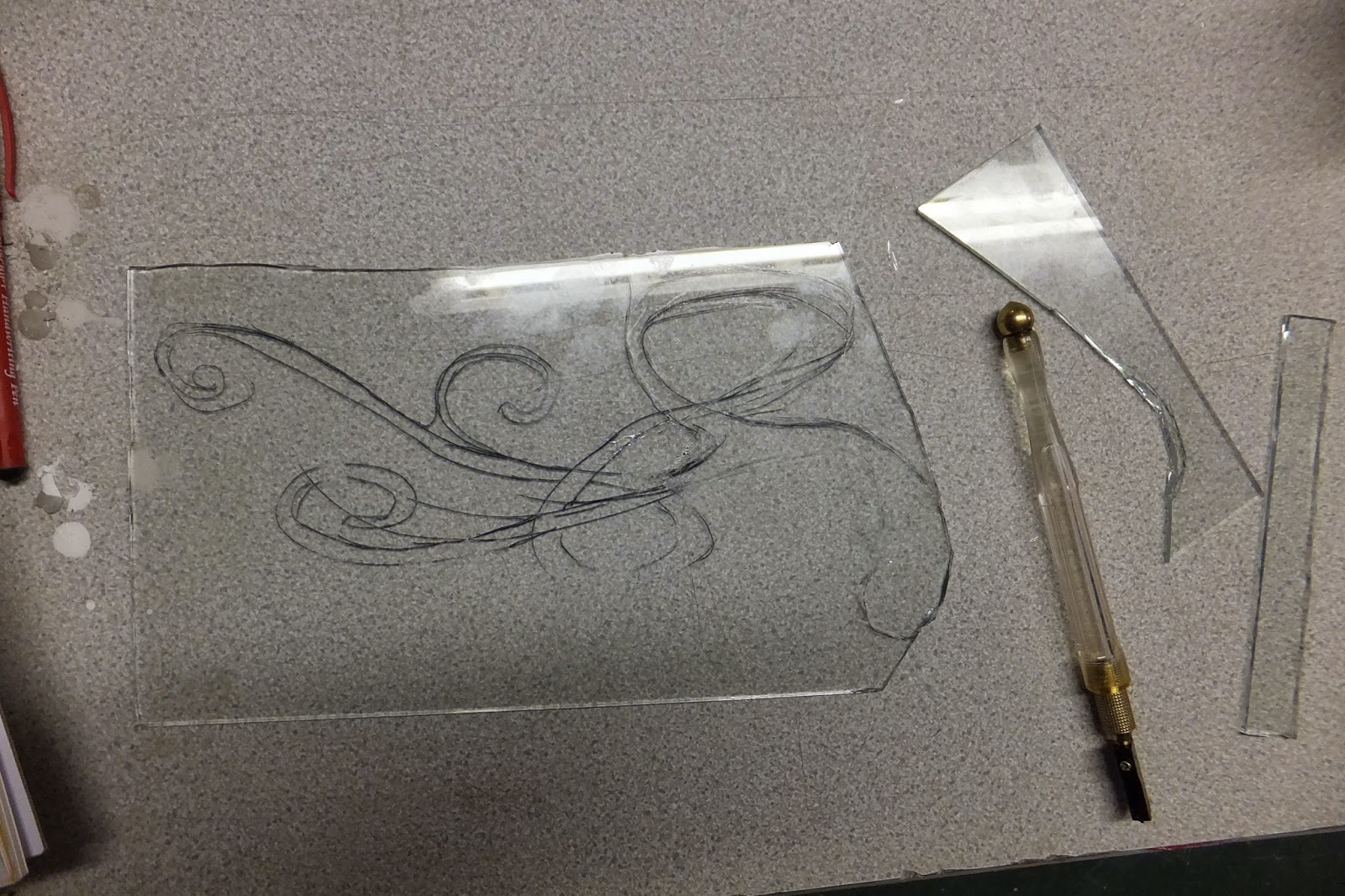

It was

now time to move my book from 3D all the way to the art room. Some of the

tutors helped to move it. We managed to get it through the hall and up some

small stairs. After placing it in the room, we could then set up the projector.

Once the pictures were clear and the sizing had been sorted, I could then start

on my letters. After spraying them outside and letting them dry, I could stick

them to the other side of my book. I placed the letters as if they were on the

page, then made them peel off, distorting them so they were more difficult to

recognise as letters. I had very little time to do this. I found it hard to fix

the letters on using fishing wire. What I needed was a stronger line that would

hold the letters in place without having to tie them to anything.

It was

now time to move my book from 3D all the way to the art room. Some of the

tutors helped to move it. We managed to get it through the hall and up some

small stairs. After placing it in the room, we could then set up the projector.

Once the pictures were clear and the sizing had been sorted, I could then start

on my letters. After spraying them outside and letting them dry, I could stick

them to the other side of my book. I placed the letters as if they were on the

page, then made them peel off, distorting them so they were more difficult to

recognise as letters. I had very little time to do this. I found it hard to fix

the letters on using fishing wire. What I needed was a stronger line that would

hold the letters in place without having to tie them to anything.